The Beatles Break-up: A Quick Guide

The Beatles’ breakup is the most misunderstood topic debated by fans online, shaped by inaccuracies and agendas.

Did Yoko Ono break up The Beatles? This question has fueled decades of debate, often unfairly blaming Ono for the band’s demise. Social media has amplified this narrative, spreading half-truths and hostility.

In reality, Yoko Ono didn’t break up The Beatles — the band broke up themselves. While John and Yoko’s relationship played a role, it wasn’t the decisive factor; their breakup was a complex, years-long process driven by deeper issues.

To truly understand the breakup, we need to move past myths and urban legends and consider four key factors:

McCartney’s dominance after Brian Epstein’s death.

The rise and fall of the ill-fated Apple Corps.

The group’s personal and creative evolution as individuals.

The hiring of the controversial manager Allen Klein.

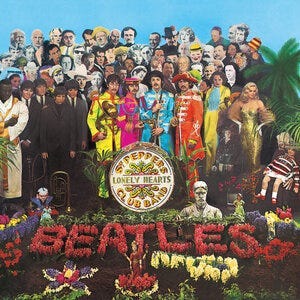

Ironically, their downfall began while making what many consider the greatest album of all time: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

The McCartney Era Begins

While The Beatles were on a retreat learning transcendental meditation, their manager, Brian Epstein, passed away at the age of 32 from an accidental overdose of sedatives. His death impacted both the personal and professional lives of the band. The band faced an uncertain future without Brian, who had been the group’s greatest champion before their fame and their unwavering north star through the uncharted waters of Beatlemania.

Adding to the uncertainty, his death occurred during a period of major transition for the group. They had just released Sgt. Pepper’s, marking the start of The Beatles’ “McCartney era,” which intensified significantly after Brian’s passing.

In hindsight, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band began tensions that would soon reach a breaking point. The album was undeniably a musical masterpiece, with each member contributing innovative ideas. However, it also signaled a major shift in the band’s dynamic, as Paul McCartney took significant control over the rest of the group for various reasons.

The concept for the album was predominately Paul’s.

Paul was in an era of rapid artistic growth.

While still brilliant, Lennon’s creative output had begun to slow.

George Harrison’s focus on Eastern music made him less invested in McCartney’s direction for the record and the group.

After Brian’s death, the band struggled with grief, and McCartney threw himself into work, leading to another Paul-driven project: Magical Mystery Tour. This was the first of several Beatle-adjacent ventures, including the animated film Yellow Submarine, where the band had little involvement beyond the soundtrack. These projects foreshadowed the growing internal chaos that would define the White Album sessions in 1968, yet despite the instability, they continued under McCartney’s increasing leadership.

In 1968, they launched their most ambitious project, Apple Corps, which would ultimately turn disastrous and haunt them long after their breakup.

The Rotting Apple Corps

Instead of hiring a new manager to provide the business expertise Apple Corps required, John, Paul, George, and Ringo moved forward with a bold but flawed business plan conceived prior to Epstein’s death to act as a tax haven and a pet project for the group.

Lennon recalled, “Our accountant came up and said, ‘We’ve got this amount of money. Do you want to give it to the government or do something with it?’ So we decided to play businessmen for a bit. Apple was going to be records, films, and electronics — which all tie up.”

According to TheBeatles.com archive, Apple’s purpose was “an artist-orientated mission [which] celebrated diversity in a friendly, creative environment.” Essentially, The Beatles aimed to overhaul the traditional music business model, offering a platform to artists who would typically be overlooked and providing opportunities that were otherwise unavailable to them.

Without Brian Epstein to oversee it, Apple Corps was doomed from the start. Its poorly managed structure heightened personal and financial troubles while each Beatle pursued personal interests.

McCartney focused on building Apple Records, appointing Peter Asher as head of A&R, which led to the signing of James Taylor and Badfinger (a group championed by roadie Mal Evans).

Lennon explored avant-garde projects, such as releasing his experimental work with Yoko Ono, “Two Virgins.”

Harrison pursued Eastern music and released an electronic record.

Ringo experimented with his love of films with Apple Films releasing “Born to Boogie,” about the band T. Rex.

Beyond music and film, Apple Corps also incorporated an electronics division, hiring Alex Mardas, a.k.a. “Magic Alex,” who promised futuristic innovations (which never came to fruition) and was commissioned to build Apple a state-of-the-art studio. These efforts collapsed spectacularly, wasting vast sums of money, as depicted in the 2021 documentary Get Back.

With no financial discipline, excessive spending, and unapproved expenditures, Apple Corps quickly spiraled out of control. It hemorrhaged money, and conflicts intensified, making it clear that professional management was urgently needed to save both the band’s finances and its future as a group.

The ‘De-Klein’ of The Beatles

By 1969, The Beatles were a band in disarray. Mismanagement, clashing egos, and a lack of clear leadership outside the band had plunged their new business venture into chaos. Personal relationships between John, Paul, George, and Ringo were deteriorating under the strain of fame and creative differences. As the fabric of the Fab Four unraveled, brash businessman Allen Klein saw his chance to step in.

Klein had long eyed The Beatles, and when the chance to manage them came, he seized it. Despite his troubled partnership with The Rolling Stones, he used it as proof of his abilities. Mick Jagger warned The Beatles to avoid Klein, but John (like the others), frustrated with Paul’s dominant role, ignored the warning. Drawn to Klein’s aggressive style, John embraced his promise to fix their finances, secure better deals, and stabilize their messy business affairs.

From the start, Paul McCartney opposed Klein. Paul had his own candidate for the job: his father-in-law, Lee Eastman, a well-regarded entertainment lawyer. McCartney trusted Eastman to safeguard The Beatles’ interests. Unconvinced and wary of Paul’s insistence on control, John viewed Klein as a means to level the playing field. Harrison and Ringo, fed up with Paul’s self-appointed leadership, sided with John.

In early 1969, they hired Allen Klein as their manager, overriding Paul’s objections. Paul refused to sign Klein’s management contract, leaving him further isolated. Hiring Klein was arguably the pivotal turning point in the Beatle’s permanent demise.

While Klein immediately began renegotiating The Beatles’ record contracts and addressing their financial issues, his presence only deepened the divisions within the group behind the scenes, and sometimes even in front of the cameras.

Paul’s polished public image as the charming, upbeat Beatle hid his relentless drive to control, often clashing with John’s more passive-aggressive nature. The Get Back documentary, compiled from unused Let It Be footage, reveals the complexity of their relationship. Despite Paul’s role as the unofficial leader between ’67 and ’69, he still saw John as the band’s true leader, and likewise, John considered himself and Paul the core of The Beatles. Yet, the cracks in their once-close partnership and friendship were undeniable.

Last Act: Chaos, Courtrooms, & The Beatles Collapse

In September 1969, John dropped a bombshell: he was leaving the band. During a private meeting with Paul, Ringo, and Allen Klein, Lennon announced his decision to pursue his own creative path solely.

At Klein’s urging, John agreed to keep the news quiet to avoid disrupting ongoing negotiations, including the renewal of The Beatles’ record contract with EMI, which was intended to secure better terms for the band.

The fragile truce didn’t last. In April 1970, Paul announced his departure in a press release promoting his debut solo album. The press release included a self-conducted brief mock Q&A in which Paul confirmed he had no foreseeable plans to record with The Beatles, insinuating he had left the group. John was livid, accusing Paul of stealing his thunder and using the announcement as a publicity stunt for the “McCartney” album.

The rift between the two deepened, setting the stage for a bitter legal battle.

On December 31, 1970, McCartney filed suit in London’s High Court to dissolve The Beatles’ partnership, aiming to sever ties with Klein, shut down Apple Corps, and appoint someone independent to manage the band’s business. For Paul, Klein represented everything that had gone wrong with the band’s direction, and his legal battle was as much about reclaiming his independence as it was about ending The Beatles.

You Never Give Me Your Money: The Lawsuits

Paul’s legal team, focused on Klein’s financial misconduct. They accused Klein of inflating his commissions and highlighted his recent conviction for U.S. tax fraud. The strategy was effective, painting Klein as being opportunistic and detrimental to the Beatle’s business partnership.

Klein and the other Beatles argued that his appointment was legitimate, brushing off Paul’s complaints as “just business.” But Klein’s defensive attitude and constant shifting of blame damaged his credibility.

On March 12, 1971, the court ruled in McCartney’s favor, criticizing Klein’s shady financial practices and declaring the partnership irreparable. This was especially true since the band wasn’t working together anymore but still sharing profits from their solo records and albums released under the Apple Records label. As a result, the court appointed an independent party to take control of The Beatles’ finances.

Although John, George, and Ringo initially appealed the decision, The Beatles’ partnership was officially dissolved in 1975.

Eventually, Lennon admitted McCartney’s instincts about Klein were correct, going so far as to lyrically tear Klein apart in the song “Steel and Glass” from his 1974 album Walls and Bridges.

And in The End

The Beatles’ breakup was messy, painful, and agonizingly prolonged. To borrow from Hemingway, the Beatles broke up “Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

While fans may never agree on the cause, one thing is clear: The breakup began long before Yoko appeared. It was the inevitable result of a group that started in 1957 as boys and grew into men. Like any relationship, theirs evolved, and they naturally grew apart. Yes, Allen Klein played a key role, Yoko added tension, and Paul could be demanding.

Ultimately, The Beatles’ split was the natural end of a partnership that had run its course, leaving behind a legacy unmatched in music history. They ended their creative journey at the peak of their artistic powers, leaving us with a timeless catalog of songs that remain as vibrant today as ever.

As always, thanks for reading.

-Daniel

Enjoyed this piece? The author has more to share — read the original post on Rock n’Heavy and discover his work here.

Well written and even handed about each of the Beatles needing to grow in new directions. As it is, they left us each wanting just a little bit more and being thankful for their time together.🌹